Feb

Poland, the seventh largest country in Europe, occupies an area of 120,727 square miles—some-what larger than the state of Nevada. Located in east-central Europe, it is bordered to the east by Russia and the Ukraine, the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south, Germany to the west, and the Baltic Sea to the north. Drained by the Vistula and Oder Rivers, Poland is a land of varied land-scape—from the central lowlands, to the sand dunes and swamps of the Baltic coast, to the mountains of the Carpathians to the south. Its 1990 population of just over 38 million is largely homogeneous ethnically, religiously, and linguistically. Minority groups in the country include Germans, Ukrainians and Belarusans. Ninety-five percent of the population is Roman Catholic, and Polish is the national language. Warsaw, located in the central lowlands, is the nation’s capital. Poland’s national flag is bicolor: divided in half horizontally, it has a white stripe on the top half and a red one on the bottom. Polish Americans often display a flag similar to this with a crowned eagle at its center.

HISTORY

The very name of Poland harkens back to its origins in the Slavic tribes that inhabited the Vistula valley as early as the second millennium B.C. Migrations of these tribes resulted in three distinct subgroups: the West, East, and South Slavs. It was the West Slavs who became the ancestors of modern Poles, settling in and around the Oder and Vistula valleys. Highly clannish, these tribes were organized in tight kinship groups with commonly held property and a rough-and-ready sort of representative government regarding matters other than military. These West Slavs slowly joined in ever-larger units under the pressure of incursions by Avars and early Germans, ultimately being led by a tribe known as the Polanie. From that point on, these West Slavs, and increasingly the entire region, were referred to as Polania or later, Poland. Under the Polanian duke Mieszko and his Piast dynasty, further consolidation around what is modern Poznan created a true state; and in 966, Mieszko was converted to Christianity. It is this event that is commonly accepted as the founding date of Poland. It is doubly important because Mieszko’s conversion to Christianity— Roman Catholicism—would link Poland’s fortunes in the future to those of Western Europe. The East Slavs, centered at Kiev, were converted by missionaries from the Greek church, which in turn linked them to the Orthodox east.

Meanwhile, the South Slavs had been coalescing into larger units, forming what is known as Little Poland, as opposed to Great Poland of the Piasts. These South Slavs joined Great Poland under Casimir I and for several generations the new state thrived, checking the tide of German expansionism. But from the twelfth to thirteenth centuries, the new kingdom became fragmented by a duchy system that created political chaos and civil war among rival princes of the Piast lineage. Following devastations caused by Tatar invasions in the early thirteenth century, Poland was defenseless against a further tide of German settlement. One of the last Piasts, Casimir III, succeeded in reunifying the kingdom in 1338, and in 1386 it came under the rule of the Jagiellonian dynasty when the grand duke of Lithuania married the crown princess of the Piasts, Jadwiga. Known as Poland’s Golden Age, the next two centuries of Jagiellonian rule enabled Poland-Lithuania to become the dominant power in central Europe, encompassing Hungary and Bohemia in its sphere of influence and producing a rich cultural heritage for the nation, including the achievements of such individuals as Copernicus (Mikołaj Kopernik, 1473-1543). At the same time, Poland enjoyed one of the most representative governments of its day as well as the most tolerant religious climate in Europe.

But with the end of the Jagiellonian dynasty in 1572, the kingdom once again fell apart as the landed gentry increasingly assumed local control, sapping the strength of the central government in Krakow. This state of affairs continued for two centuries until Poland was so weakened that it suffered three partitions: Austria took Galicia in 1772; Prussia acquired the northwestern section in 1793; and Tsarist Russia possessed the northeastern section in 1795). By the end of the three partitions, Poland had been completely wiped off the map of Europe. There would not be an independent Poland again for a century and a half, though a nominal Kingdom of Poland was established within the Russian Empire by the Congress of Vienna in 1815. In both Russia and Germany a strict policy of suppression of the Polish language and autonomous education was enforced.

After World War I, an independent Poland was once again re-established. With Josef Pilsudski (1867-1935) as its president and dictator from 1926 to 1935, Poland maintained an uneasy peace with the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. But with the onset of World War II, Poland was the first victim, and once again the nation was subsumed into other countries: Germany and the Soviet Union initially, and then solely under German rule. The Nazis used Poland as a killing ground to subdue and eradicate Polish culture by executing its intellectuals and nobles, and to “settle” the Jewish question once and for all by exterminating the Jews of Europe. In camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau this gruesome strategy was put into effect, and by the end of the war in 1945, Poland had lost a fifth of its population, half of which—over three million—were Jews.

Liberation, however, did not mean freedom, for after the war Poland fell under the Soviet sphere; a communist state was set up and Poland once again had become a fiefdom to a foreign power. In 1956 Poland’s workers went on a general strike in protest to Moscow’s heavy-handed domination. Though brutally suppressed, the strike did force Poland’s new leader Wladysław Gomułka to relax some of the totalitarian controls imposed by Warsaw and Moscow, and farms were decollectivized. Through successive leadership of Edward Gierek and General Wojciech Jaruzelski, however, the economic conditions worsened and the Poles struggled increasingly for more autonomy from Moscow. By 1980 three events had coincided that would be decisive for Poland’s future: the Soviet Union was going bankrupt; Karol Cardinal Wojtyła became Pope John Paul II; and a new and illegal union, Solidarity, had been formed under Lech Wałesa. These last two especially brought Poland into international focus. By 1989, Solidarity won concessions from the government including participation in free elections. After their overwhelming victory, which brought to power their leader Lech Wałesa as President, Solidarity set up a coalition government with the communists; and with the fall of the Soviet Union, Poland along with all of central Europe, regained new breathing room in its heartland. The difficult task now confronting the country is a transformation from a centrally planned economy to a market economy, one that causes enormous dislocations including unemployment and runaway inflation.

THE FIRST POLES IN AMERICA

Poles numbered among the earliest colonists in the New World and today, as their numbers exceed ten million, they represent the largest of the Slavic groups in America. Though claims have been made for Poles sailing with Viking ships exploring the New World before 1600, there is no hard evidence to support them. By 1609, however, Polish immigrants do appear in the annals of Jamestown, having been recruited by the colony as skilled craftsmen to create products for export. These immigrants were integral in the establishment of both the glassmaking and woodworking industries in the new colonies. An early Polish explorer, Anthony Sadowski, set up a trading post along the Mississippi River which later became the city of Sandusky, Ohio. Two other names of note occur in the early history of what would become the American republic: the noblemen Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817) and Casimir Pułaski (1747-1779) both fought on the rebel side in the Revolutionary War. Pulaski, killed in the battle of Savannah, is still honored by Polish Americans—Polonia as the ethnic community is referred to—by annual marches on October 11, Pulaski Day.

SIGNIFICANT IMMIGRATION WAVES

Since the times of those earliest Polish settlers— romantics, adventurers and men simply seeking a better economic life—there have been four distinct waves of immigration to the United States from Poland. The first and smallest, occasioned by the partitioning of Poland, lasted from roughly 1800 to 1860 and was largely made up of political dissidents and those who fled after the dissolution of their national homeland. The second wave was far more significant and took place between 1860 and World War I. Immigrants during this time were in search of a better economic life and tended to be of the rural class, so-called za chleben (for bread) emigrants. A third wave lasted from the end of World War I through the end of the Cold War and again comprised dissidents and political refugees. Since the fall of the Soviet Union and Poland’s democratic reforms, there has been yet a fourth wave of a seemingly more temporary immigrant group, the wakacjusze, or those who come on tourists visas but find work and stay either illegally or legally. These economic immigrants generally plan to earn money and return to Poland.

The first wave of immigrants, from approximately 1800 to 1860, was largely made up of intellectuals and lesser nobility. Not only the partitioning of Poland, but insurrections in 1830 and 1863 also forced political dissidents from their Polish homeland. Many fled to London, Paris and Geneva, but at the same time New York and Chicago also received its share of such refugees from political oppression. Immigration figures are always a problematic issue, and those for Polish immigrants to the United States are no different. For much of the modern era there was no political entity such as Poland, so immigrants coming to America had an initial difficulty in describing their country of origin. Also, there was with Poles, more so than other ethnic immigrant groups, more back-and-forth travel between host country and home country. Poles have tended to save money and return to their native country in higher numbers than many other ethnic groups. Additionally, minorities within Poland who immigrated to the United States confuse the picture. Nonetheless, what numbers that exist from U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service records indicate that fewer than 2,000 Poles immigrated to the United States between 1800 and 1860.

The second wave of immigration was inaugurated in 1854 when about 800 Polish Catholics from Silesia founded Panna Maria, a farming colony in Texas. This symbolic opening of America to the Poles also opened the flood gates of immigration. The new arrivals tended to cluster in industrial cities and towns of the Midwest and Middle Atlantic States—New York, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Detroit, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Chicago, and St. Louis—where they became steelworkers, meatpackers, miners, and later autoworkers. These cities still retain their large contingents of Polish Americans. A lasting legacy of these Poles in America is the vital role they played in the growth and development of the U.S. labor movement, Joseph Yablonski of the United Mine Workers only one case in point.

Confusion over exact numbers of Polish immigrants again becomes a problem during this period, with large under reporting, especially during the 1890s when immigration was highest. Most agree, however, that between mid-nineteenth century and World War I, some 2.5 million Poles immigrated to the United States. This wave of immigration can be further broken down to two successive movements of Poles from different regions of their partitioned

country. The first to come were the German Poles, who tended to be better educated and more skilled craftsmen than the Russian and Austrian Poles. High birthrates, overpopulation, and large-scale farming methods in Prussia, which forced small farmers off the land, all combined to send German Poles into emigration in the second half of the nineteenth century. German policy vis-a-vis restricting the power of the Catholic church also played a part in this exodus. Those arriving in the United States totalled roughly a half million during this period, with numbers dwindling by the end of the century.

However, just as German Polish immigration to the United States was diminishing, that of Russian and Austrian Poles was just getting underway. Again, overpopulation and land hunger drove this emigration, as well as the enthusiastic letters home that new arrivals in the United States sent to their relatives and loved ones. Many young men also fled from military conscription, especially in the years of military build-up just prior to and including the onset of World War I. Moreover, the journey to America itself had become less arduous, with shipping lines such as the North German Line and the Hamburg American Line now booking passage from point to point, combining overland as well as transatlantic passage and thereby simplifying border crossings. Numbers of Galician or Austrian Poles total approximately 800,000, and of Russian Poles—the last large immigration contingent— another 800,000. It has also been estimated that 30 percent of Galician and Russian Poles arriving between 1906 and 1914 returned to their homelands.

The influx of such large numbers of one ethnic group was sure to cause friction with the “established” Americans, and during the last half of the nineteenth century history witnesses intolerance toward many of the immigrants from divergent parts of Europe. That the Poles were strongly Catholic contributed to such friction, and thus Polonia or the Polish Americans formed even tighter links with each other, relying on ethnic cohesiveness not only for moral support, but financial, as well. Polish fraternal, national, and religious organizations such as the Polish National Alliance, the Polish Union, the Polish American Congress, and the Polish Roman Catholic Union have been instrumental in not only maintaining a Polish identity for immigrants, but also in obtaining insurance and home loans to set the new arrivals on their own feet in their new country. Such friction abated as Poles assimilated in their host country, to be supplanted by new waves of immigrants from other countries. Polish Americans have, however, continued to maintain a strong ethnic identity into the late twentieth century.

With the end of World War I and the re-establishment of an independent Polish state, it was believed that there would be a huge exodus of Polish immigrants returning to their homeland. Such an exodus did not materialize, though immigration over the next generation greatly dropped off. U.S. immigration quotas imposed in the 1920s had much to do with this, as did the Great Depression. But political oppression in Europe between the wars, displaced persons brought on by World War II, and the flight of dissidents from the communist regime did account for a further half million immigrants— many of them refugees—from Poland between 1918 and the late 1980s and the fall of communism.

The fourth wave of Polish immigration is now underway. This is comprised mostly of younger people who grew up under communism. Though not significant in numbers because of immigration quotas, this newest wave of post-Cold War immigrants, whether they be the short-term workers, wakacjusze, or long-term residents, continue to add new blood to Polish Americans, ensuring that the ethnic community continues to have foreign-born Poles among its contingent. Estimates from the 1970 census placed the number of either foreign born Poles or native born with at least one Polish parent at near three million. Over eight million claimed Polish ancestry in their background in the 1980 census and 9.5 million did so in the 1990 census, 90 percent of whom were concentrated in urban areas. A large part of such identity and cohesiveness was the result of outside conditions. It has been noted that initial friction between Polish immigrants and “established” Americans played some part in this inward looking stance. Additionally, such commonly held beliefs as folk culture and Catholicism provided further incentives for communalism. Newly arrived Poles generally had their closest contacts outside Polish Americans with their former European neighbors: Czechs, Germans, and Lithuanians. Over the years there has been a degree of friction specifically between the Polish American community and Jews and African Americans. However, during the years of partition, Polish Americans kept alive the belief in a free Poland. Such cohesiveness was further heightened in the Polish American community during the Cold War, when Poland was a satellite of the Soviet Union. But since the fall of the Soviet empire and with free elections in Poland, this outer threat to the homeland is no longer a factor in keeping Polish Americans together. The subsequent increase in immigration of the fourth wave of younger Poles escaping difficult transition times at home has added new numbers to immigrants in the United States, but it is yet to be seen what their effect will be on Polish Americans. As yet, these recent immigrants have played no part in the power structure—not being members of the fraternal organizations. What their effect in the future will be is unclear.

Acculturation and Assimilation

In a society so homogenized by the effects of mass media, such ethnic enclaves as the amorphous reaches of Polish Americans is clearly affected. Despite the recent emphasis on multiculturalism and a resurgent interest in ethnic roots, Polish Americans like other ethnic groups become assimilated more and more rapidly. Using language as a

“W e wanted to be Americans so quickly that we were embarrassed if our parents couldn’t speak English. My father was reading a Polish paper. And somebody was supposed to come to the house. I remember sticking it under something. We were that ashamed of being foreign.”

Louise Nagy in 1913, cited in Ellis Island: An Illustrated History of the Immigrant Experience, edited by Ivan Chermayeff et al. (New York: Macmillan, 1991). measure, it can be seen how quickly such absorption occurs. In a 1960 survey of children of Polish ethnic leaders, 20 percent reported that they spoke Polish regularly. By 1990, however, the U.S. census reported that only 750,000 Polish Americans spoke Polish in the home.

As part of the European emigration, Polish immigrants have had an easier time racially than many other non-European groups in assimilating or blending into the American scene. But this is only a surface assimilation. Culturally, the Polish contingent has held tightly to its folk and national roots, making Polonia more than simply a name. It has been at times a country within a country, Poland in the New World. By and large, Poles have competed

well and succeeded in their new homeland; they have thrived and built homes and raised families, and in that respect have participated in and added to the American dream. Yet this process of assimilation has been far from smooth as witnessed by one fact: the Polish joke. Such jokes have at their core a negative representation of the Poles as backward and uneducated simpletons. It is perhaps this stereotype that is hardest for Polish Americans to combat, and is a legacy of the second wave of immigrants, the largest contingent between 1860 and 1914 made up of mostly people from Galicia and Russia. Though recent studies have shown Polish Americans to have high income levels as compared to British, German, Italian, and Irish immigrant groups, the same studies demonstrate that they come in last in terms of occupation and education. For many generations, Polish Americans in general did not value higher education, though such a stance has changed radically in the late twentieth century. The professions are now heavily represented with Polish Americans as well as the blue collar world. Yet the Polish joke persists and Polish Americans have been actively fighting it in the past two decades with not only educational programs but also law suits when necessary. The days of Polish Americans anglicizing their names seem to be over; along with other ethnic groups Polish Americans now talk of ethnic pride.

TRADITIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS

It had been noted that clans and kinship communities were extremely important in the early formation of Slavic tribes. This early form of communalism has been translated into today’s world by the plethora of Polish American fraternal organizations. By the same token, other traditions out of the Polish rural and agrarian past still hold today.

Gospodarz may well be one of the prettiest sounding words in the Polish language—to a Pole. It means a landowner, and it is the land that has always been important in Poland. Ownership of land was one of the things that brought the huge influx of Poles to the United States, but less than ten percent achieved that dream, and these were mainly the German Poles who came first when there was still a frontier to carve out. The remaining Poles were stuck in the urban areas as wage-earners, though many of these managed to save the money to buy a small plot of land in the suburbs. Contrasted to this is the Górale, or mountaineer. To the lowlanders of Greater Poland, the stateless peoples of the southern Carpathians represented free human spirit, unbridled by convention and laws. Both of these impulses runs through the Polish peoples and informs their customs.

An agrarian people, many Poles have traditions and beliefs that revolve around the calendar year, the time for sowing and for reaping. And inextricably linked to this rhythm is that of the Catholic church whose saints’ days mark the cycle of the year. A strong belief in good versus evil resulted in a corresponding belief in the devil: witches who could make milk cows go dry; the power of the evil eye, which both humans and animals could wield; the belief that if bees build a hive in one’s house, the house will catch on fire; and the tradition that while goats are lucky animals, wolves, crows and pigeons all bring bad luck.

PROVERBS

Polish proverbs display the undercurrents of the Polish nature, its belief in simple pragmatism and honesty, and a cynical distrust of human nature: When misfortune knocks at the door, friends are asleep; the mistakes of the doctor are covered by the earth; the rich man has only two holes in his nose, the same as the poor man; listen much and speak little; he whose coach is drawn by hope has poverty for a coachman; if God wills, even a cock will lay an egg; he who lends to a friend makes an enemy; no fish without bones; no woman without a temper; where there is fire, a wind will soon be blowing.

CUISINE

The diet of Polish Americans has also changed over the years. One marked change from Poland is the increased consumption of meat. Polish sausages, especially the kielbasa —garlic-flavored pork sausage—have become all but synonymous with Polish cuisine. Other staples include cabbage in the form of sauerkraut or cabbage rolls, dark bread, potatoes, beets, barley, and oatmeal. Of course this traditional diet has been added to by usual American fare, but especially at festivities and celebrations such as Christmas and Easter, Polish Americans still serve their traditional food. Polish Americans have, in addition to the sausage, also contributed staples to American cuisine, including the breakfast roll, bialys, the babka coffeecake, and potato pancakes.

TRADITIONAL COSTUMES

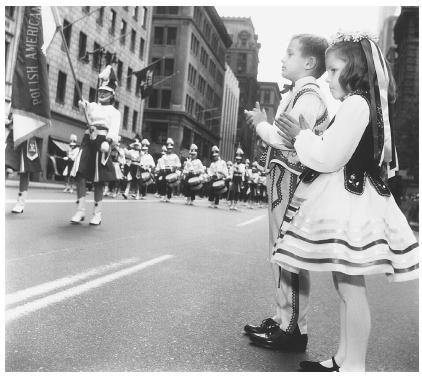

Traditional clothing is worn less and less by Polish Americans, but such celebrations as Pulaski Day on October 11 of each year witness upwards of 100,000 Polish Americans parading between 26th Street and 52nd Street in New York, many of them wearing traditional dress. For women this means a combination blouse and petticoat covered by a full, brightly colored or embroidered skirt, an apron, and a jacket or bodice, also gaily decorated. Headdress ranges from a simple kerchief to more elaborate affairs made of feathers, flowers, beads, and ribbons decorating stiffened linen. Men also wear headdresses, though usually not as ornate as the women’s—felt or straw hats or caps. Trousers are often white with red stripes, tucked into the boots or worn with mountaineering moccasins typical to the Carpathians. Vests or jackets cover white embroidered shirts, and the favorite colors replicate the flag: red and white.

HOLIDAYS

In addition to Pulaski Day, which President Harry Truman decreed an official remembrance day in 1946, Polish American celebrations consist mainly of the prominent liturgical holidays such as Christmas and Easter. The traditional Christmas Eve dinner, called wigilia, begins when the first star of the evening appears. The dinner, which is served upon a white tablecloth under which some straw has been placed, consists of 12 meatless courses—one for each of the apostles. There is also one empty chair kept at the table for a stranger who might chance by. This vigil supper begins with the breaking of a wafer, the oplatek, and the exchange of good wishes; it moves on to such traditional fare as apple pancakes, fish, pierogi or a type of filled dumpling, potato salad, sauerkraut and nut or poppy seed torte for dessert. To insure good luck in the coming year one must taste all courses, and there must also be an even number of people at the table to ensure good health. The singing of carols follows the supper. In Poland, between Christmas Eve and the Epiphany (January 6, or “Three Kings”) “caroling with the manger” takes place in which carolers bearing a manger visit neighbors and are rewarded with money or treats. In Poland, the Christmas season comes to a close with Candelmas day on February 2, when the candles are taken to church to be blessed. It is believed that these blessed candles will protect the home from sickness or bad fortune.

The Tuesday before Ash Wednesday is celebrated by much feasting. Poles traditionally fried pą1451czki (fruit-filled doughnuts) in order to use the sugar and fat in the house before the long fast of Lent. In the United States, especially in Polish communities, the day before Ash Wednesday has become popularized as Pączki Day; Poles and non-Poles alike wait in line at Polish bakeries for this pastry. Easter is an especially important holiday for Polish Americans. Originally an agrarian people, the Poles focussed on Easter as the time of rebirth and regeneration not only religiously, but for their fields as well. It marked the beginning of a farmer’s year. Consequently, it is still celebrated with feasts which include meats and traditional cakes, butter molded into the shape of a lamb, and elaborately decorated eggs ( pisanki ), and a good deal of drinking and dancing.

HEALTH ISSUES

There are no documented health problems specific to Polish Americans. Initially skeptical of modern medicine and more likely to try traditional home cures, Polish Americans soon were converted to the more modern practices. The creation of fraternal and insurance societies such as the Polish National Alliance in 1880, the Polish Roman Catholic Union in 1873, and the Polish Women’s Alliance in 1898, helped to bring life insurance to a larger segment of Polonia. As with the majority of Americans, Polish Americans acquire health insurance at their own expense, or as part of a benefits package at their place of employment.

Language

Polish is a West Slavic language, part of the Lekhite subgroup, and is similar to Czech and Slovak. Modern Polish, written in the Roman alphabet, stems from the sixteenth century. It is still taught in Sunday schools and parochial schools for children. It is also taught in dozens of American universities and colleges. The first written examples of Polish are a list of names in a 1136 Papal Bull. Manuscripts in Polish exist from the fourteenth century. Its vocabulary is in part borrowed from Latin, German, Czech, Ukrainian, Belarusan, and English. Dialects include Great Polish, Pomeranian, Silesian and Mazovian. Spelling is phonetic with every letter pronounced. Consonants in particular have different pronunciation than in English. “Ch,” for example is pronounced like “h” in horse; “j” is pronounced like “y” at the beginning of a word; “cz” is pronounced “ch” as in chair; “sz” is pronounced like “sh” as in shoe; “rz” and “z” are pronounced alike as the English “j” in jar; and “w” is pronounced like the English “v” in victory. Various diacriticals are also used in Polish: “ż,” “ź,” “ń,” “ć,” “ś,” “ą,” “ę,” and “ł.”

GREETINGS AND OTHER POPULAR EXPRESSIONS

Typical Polish greetings and other expressions include: Dzien dobry (“gyen dobry”)—Good morning; Dobry wieczor (“dobry viechoor”)—Good evening; Dowidzenia (“dovidzenyah”)—Good-bye; Dozobaczenia (“dozobahchainya”)—Till we meet again; Dziekuje (“gyen-kuyeh”)—Thank you; Przepraszam (“psheprasham”)—I beg your pardon; Nie (“nyeh”)—No; Tak (“tahk”)—Yes.

Family and Community Dynamics

Typically, the Polish family structure is strongly nuclear and patriarchal. However, as with other ethnic groups coming to America, Poles too have adapted to the American way of life, which means a stronger role for the woman in the family and in the working world, with a subsequent loosening of the strong family tie. Initially, single or married men were likely to immigrate alone, living in crowded quarters or rooming houses, saving their money and sending large amounts back to Poland. That immigration trend changed over the years, to be replaced by family units immigrating together. In the 1990s, however, the immigration pattern has come full circle, with many single men and women coming to the United States in search of work.

Until recently, Polish Americans have tended to marry within the community of Poles, but this too has changed over the years. A strong ethnic identity is maintained now not so much through shared traditions or folk culture, but through national pride. As with many European immigrant groups, male children were looked upon as the breadwinners and females as future wives and mothers. This held true through the second wave of immigrants, but with the third wave and with second and third generation families, women in general took a more important role in extra-familial life.

As with many other immigrant groups, the Poles maintain traditions most closely in those ceremonies for which the community holds great value: weddings, christenings and funerals. Weddings are no longer the hugely staged events of Polish heritage, but they are often long and heavy-drinking affairs, involving several of the customary seven steps: inquiry and proposal; betrothal; maiden evening and the symbolic unbraiding of the virgin’s hair; baking the wedding cake; marriage ceremony; putting to bed; and removal to the groom’s house. Traditional dances such as the krakowiak, oberek, mazur, and the zbo’jnicki will be enjoyed at such occasions, as well as the polka, a popular dance

among Polish Americans. (The polka, however, is not a Polish creation.) Also to be enjoyed at such gatherings are the national drink, vodka, and such traditional fare as roast pork, sausages, barszcs or beet soup, cabbage rolls and poppy seed cakes.

Christenings generally take place within two weeks of the birth on a Sunday or holiday; and for the devoutly Catholic Poles, it is a vital ceremony. Godparents are chosen who present the baby with gifts, more commonly money now than the traditional linens or caps of rural Poland. The christening feast, once a multi-day affair, has been toned down in modern times, but still involves the panoply of holiday foods. The ceremony itself may include a purification rite for the mother as well as baby, a tradition that goes back to the pre-Christian past.

Funerals also retain some of the old traditions. The word death in Polish (śmierċ) is a feminine noun, and is thought of as a tall woman draped in white. Once again, Catholic rites take over for the dead. Often the dead are accompanied in their coffins by strong shoes for the arduous journey ahead or by money as an entrance fee to heaven. The funeral itself is followed by a feast or stypa which may also include music and dancing.

EDUCATION

Education has also taken on more importance. Where a primary education was deemed sufficient for males in the early years of the twentieth century— much of it done in Catholic schools—the value of a university education for children of both sexes now mirrors the trend for American society as a whole. A 1972 study from U.S. Census statistics showed that almost 90 percent of Polish Americans between the ages of 25 and 34 had graduated from high school, as compared to only 45 percent of those over age 35. Additionally, a full quarter of the younger generation, those between the ages 25 and 34, had completed at least a four-year university education. In general, it appears that the higher socio-economic class of the Polish American, the more rapid is the transition from Polish identity to that of the dominant culture. Such rapid change has resulted in generational conflict, as it has throughout American society as a whole in the twentieth century.

Religion

Poland is a largely Catholic nation, a religion that survived even under the anti-clerical reign of the communists. It is a deeply ingrained part of the Polish life, and thus immigrants to the United States brought the religion with them, Initially, Polish American parishes were established from simple meetings of the local religious in stores or hotels. These meetings soon became societies, taking on the name of a saint, and later developed into the parish itself, with priests arriving from various areas of Poland. The members of the parish were responsible for everything: financial support of their clergy as well as construction of a church and any other buildings needed by the priest. Polish American Catholics were responsible for the creation of seven religious orders, including the Resurrectionists and the Felicians who in turn created schools and seminaries and brought nuns from Poland to help with orphanages and other social services.

Quickly the new arrivals turned their religious institution into both a parish and an okolica, a local area or neighborhood. There was rapid growth in the number of such ethnic parishes: from 17 in 1870 to 512 only 40 years later. The number peaked in 1935 at 800 and has tapered off since, with 760 in 1960. In the 1970s the level of church attendance was beginning to drop off sharply in the Polish American community, and the use of English in the mass was becoming commonplace. However, the newest contingent of Polish refugees has slowed this trend, raising attendance once again, and helping to restore masses in the Polish language at many churches.

All was not smooth for the Polish American Catholics. A largely Protestant nation in the nineteenth century, America proved somewhat intolerant of Catholics, a fact that only served to separate immigrant Poles from the mainstream even more. Also, within the church, there was dissension. Footing all the bills for the parish, still Polish American Catholics had little representation in the hierarchy. Such disputes ultimately led to the establishment of the Polish National Church in 1904. The founding bishop, Reverend Francis Hodur, built the institution to 34 churches and over 28,000 communicants in a dozen years’ time.

Employment and Economic Traditions

As has been noted, the Polish immigrants were largely agrarian except for those intellectuals who fled political persecution, By and large they came the United States hoping to find a plot of land, but instead found the frontier closed and were forced instead into urban areas of the Midwest and Middle Atlantic states where they worked in steel mills, coal mines, meatpacking plants, oil refineries and the garment industry. The pay was low for such work: the average annual income for Polish immigrants in 1910 was only $325. The working day was long, as it was all across America at the time, averaging a ten-hour day. But still Polish Americans managed to save their money and by 1910 it is estimated that these immigrants had been able to send $40 million back to their relatives and loved ones in Russian and Austrian Poland. The amount was so large in fact, that a federal commission was set up to investigate the damages to the U.S. economy that such an outflow of funds might create.

Families pulled together in Polonia, with education coming second to the need for young boys to contribute to the annual income. The need for such economies began to decline after World War I, however, and by 1920 only ten percent of Polish Americans families derived income from the labor of children, and two-thirds were supported by the head of family. Over the years of the twentieth century— except for the years of the Great Depression—the economic situation of Polish Americans has steadily improved, with education taking on increasing importance, creating a parallel rise in Polish Americans in the white collar labor market. By 1970 only four percent were laborers; 23 percent were craftsmen.

Polish Americans have also been important in the formation of labor unions, not only swelling the membership, but also providing leaders such as David Dubinsky of the CIO and, as has been noted, Joseph Yablonski of the United Mine Workers.

Politics and Government

Though heavily concentrated in nine industrial states, Polish Americans did not, until the 1930s, begin to flex their political muscle. Language barriers played a part in this, but more important was the fact that earlier immigrants were too concerned with family and community issues to pay attention to the national political scene. Even in Chicago, where Polish Americans made up 12 percent of the population, they did not elect one of their own to the U.S. Congress until 1920. The first Polish American congressional representative was elected from Milwaukee in 1918.

Increasingly, however, Polish Americans have begun playing a more active role in domestic politics and have tended to vote in large numbers for the Democrats. Al Smith, a Democrat and Roman Catholic who was opposed to Prohibition, was one of the first beneficiaries of the Polish American block vote. Though he lost the election, Smith received an overwhelming majority of the Polish American vote. The Great Depression mobilized Polish Americans even more politically, organizing the Polish American Democratic Organization and supporting the New Deal policies of Franklin D. Roosevelt. By 1944 this organization could throw large numbers of Polish American votes Roosevelt’s way and were correspondingly compensated by federal patronage. Prominent Polish American members of congress have been Representatives Dan Rostenkowski and Roman Pucinski, both Democrats from Illinois, and Senator Barbara Mikulski, a Democrat from Maryland. Maine’s Senator Edmund Muskie was also of Polish American heritage.

RELATIONS WITH POLAND

Internationally Polish Americans have been more active politically than domestically. The Polish National Alliance, founded in 1880, was—in addition to being a mutual aid society—a fervent proponent of a free Poland. Such a goal manifested itself in very pragmatic terms: during World War I, Polish Americans not only sent their young to fight, but also the $250 million they subscribed in liberty bonds. Polish Americans also lobbied Washington with the objective of a free Poland in mind. The Polish American Congress (PAC) was created in 1944 to help secure independence for Poland, opposing the Yalta and Potsdam agreements, which established Soviet hegemony in Eastern Europe. During this same time, Polish American socialists formed the Pro-Soviet Polish American Council, but its power waned in the early years of the Cold War. PAC, however, fought on into the 1980s, supporting Solidarity, the union movement in Poland largely responsible for the downfall of the communist government. Gifts of food, clothing and lobbying in Washington were all part of the PAC campaign for an independent Poland and the organization has been very active in the establishment of a free market system in Poland since the fall of the communist government.

Categories

- Algebra (5)

- Apps (52)

- Articles (11)

- Asian History (4)

- Asian History Heritage (13)

- Asian History Heritage Articles (8)

- Asian History Heritage Prayer (1)

- Asian History Heritage Spotlight (9)

- Band (3)

- Biology (11)

- Black History Heritage (39)

- Black History Heritage Articles (17)

- Black History Heritage Links (6)

- Black History Heritage Prayers (12)

- Black History Heritage Spotlight (16)

- Calculus (5)

- Career Counseling (1)

- Chemistry (10)

- Chorus (3)

- Computer Science (3)

- Dance (2)

- Economics (11)

- English (11)

- English Studies (3)

- Environmental Science (12)

- Ethics & Values (13)

- Faith & Culture (12)

- Faith & Culture Articles (7)

- Faith & Culture Prayers (4)

- Faith & Culture Spotlight (4)

- Faith & Religion (9)

- FAQ (3)

- FAQ Gradebook (3)

- French (4)

- Gay, Lesbian, and Transgender (17)

- Gay, Lesbian, and Transgender – Articles (7)

- Gay, Lesbian, and Transgender – Prayers (3)

- Gay, Lesbian, and Transgender – Spotlight (10)

- Geography/Epistemology (6)

- Geometry (4)

- Health (6)

- Inclusive Curriculum at Saint Mary’s (1)

- International Languages (13)

- Irish History & European Cultures (18)

- Irish History & European Cultures – Articles (7)

- Irish History & European Cultures – Prayers (6)

- Irish History & European Cultures – Spotlight (7)

- Islamic History (4)

- Latino & Hispanic History & Heritage (25)

- Latino & Hispanic History & Heritage Articles (13)

- Latino & Hispanic History & Heritage Prayers (5)

- Latino & Hispanic History & Heritage Spotlight (17)

- Learning Management (26)

- Lectures (2)

- Literature (3)

- Marine Biology (9)

- Mathematics (15)

- Multimedia (5)

- Physical Education (2)

- Physical Education & Health (16)

- Physics (10)

- Physiology (8)

- Poetry (3)

- Psychology (10)

- Public Policy (12)

- Register to Vote! (10)

- Register to Vote! – Articles (5)

- Register to Vote! – Links (3)

- Register to Vote! – Prayers (1)

- Register to Vote! – Spotlight (2)

- Religious Studies (21)

- Science (23)

- Scripture (9)

- Senior Project (1)

- Social Justice (13)

- Social Studies (25)

- Spanish (4)

- Sports Medicine (4)

- Statistics (5)

- Student Committee (3)

- Student Committee – 2015-2016 (2)

- Technology Use Guides (8)

- Theater Arts (6)

- Trigonometry (4)

- Uncategorized (6)

- US Government (9)

- US History (10)

- Videos (6)

- Visual & Performing Arts (15)

- Visual Arts (6)

- Women History – Articles (3)

- Women History – Prayers (2)

- Women History – Spotlight (3)

- Womens History (8)

- World History (8)

- World Religions (9)

Post Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||

Categories

Archives

- March 2020 (3)

- October 2017 (3)

- September 2017 (3)

- August 2017 (2)

- April 2017 (3)

- February 2017 (13)

- September 2016 (1)

- August 2016 (1)

- May 2016 (28)

- April 2016 (9)

- March 2016 (3)

- February 2016 (94)

- January 2015 (8)

- December 2014 (12)

- September 2014 (1)

- November 2013 (1)

- October 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (2)

- April 2013 (23)

- March 2013 (14)

- February 2013 (13)

- October 2012 (1)

- September 2012 (2)

- January 2012 (1)

Recent Posts

- Distance Learning Resources March 18, 2020

- Visualizing the History of Pandemics March 15, 2020

- Visualizing the History of the World March 15, 2020

- America Georgine Ferrera October 4, 2017

- Sophie Cruz October 3, 2017